An Artist of the Floating World

by Alistair Hicks

At first sight it is difficult to believe that Sandra Kantanen’s work is based in the present. She has taken the photographer’s challenge to heart and literally stopped time— centuries ago in some idyllic Chinese “land” of mountains and water. The simplicity of her pictures encourages contemplation of trees, blossoms, mountains, and sheets of still water; but the modern eye, unused to contemplation, finds a friction under the misleadingly still surface. Though she appears to be at odds with today’s tempo and theories, her work relies on modern solutions. She has mixed photography with paint. She paints with light. One senses the old values of a slower way of life and her interest in Tibetan Buddhism—there is a visual seduction pulling the viewer into a more thoughtful world—yet the hints at chaos through the occasional wash of color and the mix of techniques that would be heresy to traditionalists seem to accept that there are flaws not only in man-made thinking patterns, but in nature itself, and even in her “idealized” vision of it. The artist is a passionate and adept exponent of the spiritual. Though she has spent many years in China and studied the ancient Chinese art of landscape, she does not share the same unflinching belief in another heavenly world with the ancients. She knows she lives in a fast-changing world, she knows her “spiritual” and “real” worlds are not static. Her work does not offer us ultimate revelation, but rather a fluid interchange between colliding worlds.

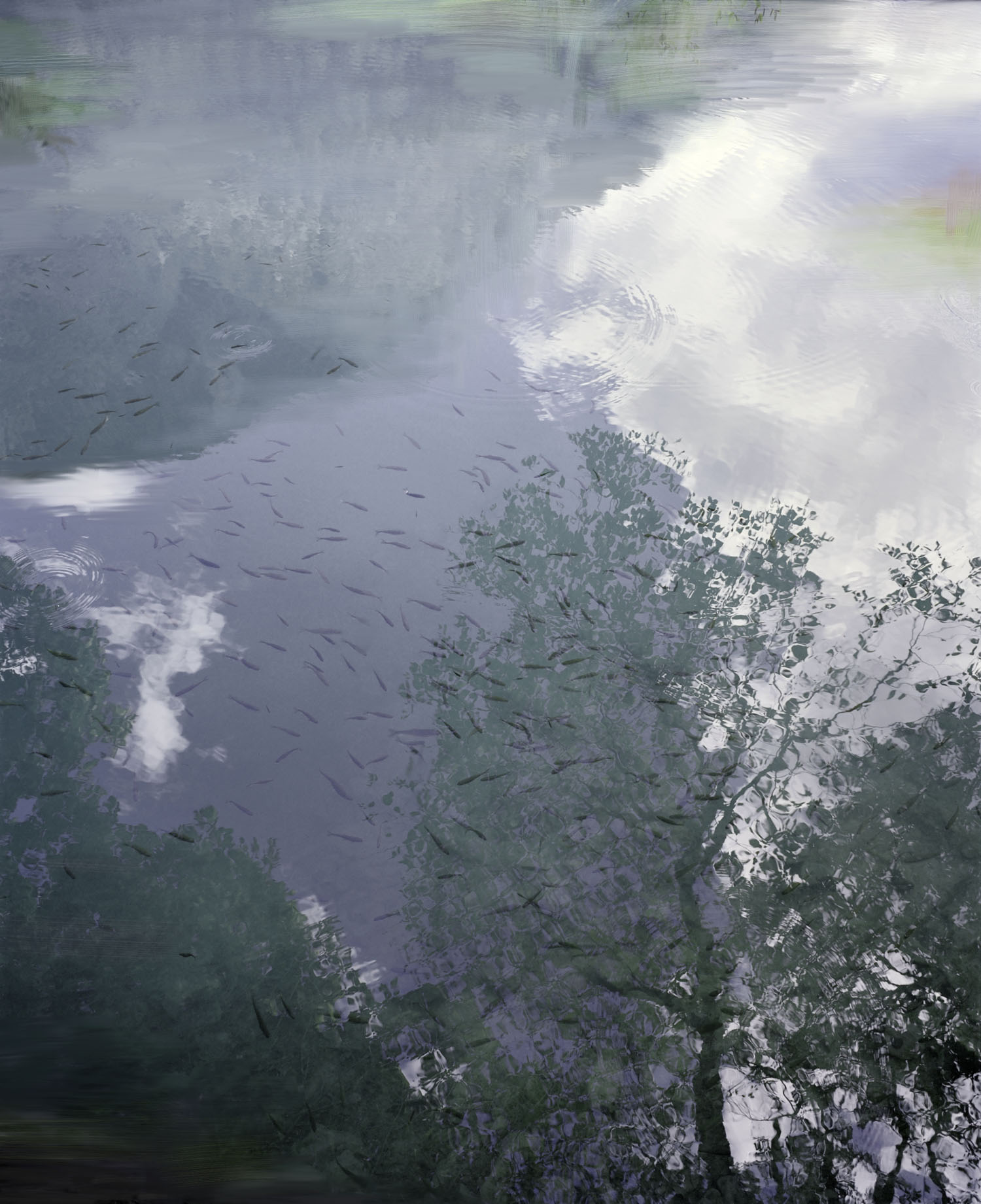

There are echoes of her former professor Jorma Puranen’s use of reflection in works such as Untitled (Lake 6, Fishpond) (2009), but the reflections have a very specific role. The fish may be swimming as countless fish depicted before have swum, but they look as if they are in the sky. They are fish out of water. Of course they are still swimming in the water, but they look as much at home in the reflected sky as in the water.

The fish are like the artist herself: she is remarkably at one with Chinese culture. “I’m not Chinese,” she writes, “but I have been wondering where I got this overwhelming feeling of belonging in that culture. I somehow had to understand it. I felt this deep sorrow for something lost when looking at their landscape.” She explains further: “I went to China originally as an exchange student in 2000 to do part of my master’s in photography. I studied Chinese landscape painting and became completely obsessed with the idea of trying to understand their way of looking at nature. As I found, most of the holy mountains they had been depicting for thousands of years were almost destroyed by pollution or otherwise turned into tourist spots. It became for me a search for a landscape that doesn’t really exist, an idealized picture.”1 Her Chinese forerunners were, of course, equally interested in an idealized depiction, not mere reproduction.

Light becomes as much a spiritual as a physical tool for Kantanen. She learned about light in a series of Morandi-like still lifes she made back in 2000. “They were a rehearsal for me,” she recalls. “I was trying to understand the nature of photography. I was interested in how the three-dimensional world transforms into two dimensions in a photograph. I figured light was all there was in this medium. I also felt I had to simplify the world I was working in. The real world was so messy, with too much information. I found landscape through China—the first time I went there. I started working with my still lifes in Beijing, I was sick in the beginning and couldn’t leave my room. The other students thought it was weird to make pictures of dead objects with white, the dead color (the Chinese see white as the color of death).”

Kantanen at times sound as if she is tilting at windmills. She quotes Andrei Tarkovsky: “Art is born and takes hold wherever there is a timeless and insatiable longing for the spiritual, for the ideal: that longing which draws people to art. Modern art has taken a wrong turn in abandoning the search for the meaning of existence in order to affirm the value of the individual for his own sake. What purports to be art begins to looks like an eccentric occupation for suspect characters who maintain that any personalized action is of intrinsic value simply as a display of self-will. But in an artistic creation the personality does not assert itself, it serves another, higher, and communal idea. The artist is always the servant, and is perpetually trying to pay for the gift that has been given to him as if by a miracle. Modern man, however, does not want to make any sacrifice, even though true affirmation of the self can only be expressed in sacrifice. We are gradually forgetting about this, and at the same time, inevitably, losing all sense of human calling.”

The last words are crucial as these photographs are not just about water, air, and rock: they investigate the human relationship with our surroundings. I don’t believe the artist is defeatist about her own age. The proof is in the positive lyricism of the work. The gently-layered compositions are affirmations of a belief in life. As Kazuo Ishiguro says in his novel An Artist of the Floating World, “It is hard to appreciate the beauty of a world when one doubts its very validity.” In borrowing his title for this short piece, I am not wanting to evoke the Edo high-life/low-life connotations of the phrase. Rather I am wishing to concentrate on the movement in Kantanen’s work. There are no fixed boundaries between her “spiritual” and “real” worlds. Tarkovsky’s vision of the dangers of unchecked individualism is no longer an unusual view. Others, such as Hou Hanru, have a more positive take on it: “Individualism is the fundamental notion of Western society: it is rooted in the worshipping of the romantic self. But somehow this generation now understands that this individuality is no longer individual, it’s not a separate subjectivity.” With each successive photograph of Kantanen’s one explores this new understanding of the individual, a new understanding of the worlds we inhabit.